A soldier in the Roman Empire in the 200s, Sebastian wisely dissembled his faith at a time when Emperor Diocletian was just starting his reign of terrible persecution of Christians. Nevertheless, his faith was detected in 286, and Diocletian had him bound to a post in a field, where archers were ordered to use him for target practice. Punctured with arrows and presumed dead, Sebastian was abandoned, until a widow came along, discovered he was still alive against impossible odds, and nursed him back to health at her house.

Once he recovered, Sebastian, motivated either by an unwavering faith or a temerarious impulse, approached Diocletian and berated him for his sins, especially his brutality toward Christians. The emperor, understandably shocked that the reportedly dead Sebastian was, indeed, alive, and even more shocked by his presumptuous animadversions, had Sebastian seized and, after refusing to abjure his religion, beaten to death with clubs. Now, every January 20, St. Sebastian is venerated by those of both the Catholic Church and the Orthodox Church as well as Anglicans and Lutherans. He is, not surprisingly, the patron saint of archers as well as plague victims and soldiers. The first representation of Sebastian dates back to the mid-500s, and for centuries thereafter he has been a popular subject in all kinds of art media, usually with the arrows that did not kill him—but not always. These are my favorites.

#1 St. Sebastian, by Pietro Paolo Christofari

The Basilica of St. Peter in Vatican City has, obviously, a tremendous number of things to see, from one of the world’s best domes to one of the world’s top portrayals of both St. Mark and St. Veronica. It also has the best work of art depicting St. Sebastian, and it’s an unusual one at that, not only for its subject, but also for its history. In the Chapel of St. Sebastian, awash in marble, I found an altar of exceptional importance. Originally, underneath it, rested the remains of saints Candidus, Innocent, Laureatus, and Victor. That group was replaced by the remains of Pope Innocent XI (1676–89), which, in 2011, were transferred to a different altar and replaced by those of Pope John Paul II (1978–2005). Above, the altarpiece was originally supposed to be a painting portraying the life of St. Peter. But things change, and Sebastian was deemed important enough to warrant his own chapel. Thus, artist Domenichino (who also painted my favorite depiction of Adam and Eve) finished his St. Sebastian, an oil on a stucco ground, by 1631. Again, things change: In 1730, Domenichino’s work was relocated to a different church, replaced by a copy created by Pietro Paolo Christofari in 1736. This newer piece portrays the martyrdom of Sebastian under Roman Emperor Diocleatian in about 288, but it’s missing the saint’s symbol: There are no arrows here. Instead, Sebastian is tied to a post, before the arrows were slung. The sign above him, “Sebastianvs Christianvs,” as well as his beard and loincloth, show a conscious effort to make Sebastian appear Christ-like. Around him, angels holding crowns and horns, Roman soldiers on horseback, and regular folk caught up in the moment in a frenzy of emotion populate the scene. It’s a masterpiece, but it’s one that almost didn’t survive: Domenichino’s original was criticized for being too crowded, overbusy, and frenetic, and he himself, dissatisfied with the work, hoped he’d be able to redo it one day, wishing the altar would fall into disrepair, necessitating a second version. Had that happened, Christofari’s copy would never exist.

The Basilica of St. Peter in Vatican City has, obviously, a tremendous number of things to see, from one of the world’s best domes to one of the world’s top portrayals of both St. Mark and St. Veronica. It also has the best work of art depicting St. Sebastian, and it’s an unusual one at that, not only for its subject, but also for its history. In the Chapel of St. Sebastian, awash in marble, I found an altar of exceptional importance. Originally, underneath it, rested the remains of saints Candidus, Innocent, Laureatus, and Victor. That group was replaced by the remains of Pope Innocent XI (1676–89), which, in 2011, were transferred to a different altar and replaced by those of Pope John Paul II (1978–2005). Above, the altarpiece was originally supposed to be a painting portraying the life of St. Peter. But things change, and Sebastian was deemed important enough to warrant his own chapel. Thus, artist Domenichino (who also painted my favorite depiction of Adam and Eve) finished his St. Sebastian, an oil on a stucco ground, by 1631. Again, things change: In 1730, Domenichino’s work was relocated to a different church, replaced by a copy created by Pietro Paolo Christofari in 1736. This newer piece portrays the martyrdom of Sebastian under Roman Emperor Diocleatian in about 288, but it’s missing the saint’s symbol: There are no arrows here. Instead, Sebastian is tied to a post, before the arrows were slung. The sign above him, “Sebastianvs Christianvs,” as well as his beard and loincloth, show a conscious effort to make Sebastian appear Christ-like. Around him, angels holding crowns and horns, Roman soldiers on horseback, and regular folk caught up in the moment in a frenzy of emotion populate the scene. It’s a masterpiece, but it’s one that almost didn’t survive: Domenichino’s original was criticized for being too crowded, overbusy, and frenetic, and he himself, dissatisfied with the work, hoped he’d be able to redo it one day, wishing the altar would fall into disrepair, necessitating a second version. Had that happened, Christofari’s copy would never exist.

#2 Saint Sebastian Interceding for the Plague Stricken, by Josse Lieferinxe

The belief that St. Sebastian was a defense against the plague boosted his importance in the Late Middle Ages. Sebsatian’s survival from his “first” martyrdom by arrows played well into this belief—arrow wounds can resemble the buboes that were symptoms of bubonic plague. That comes to the fore in Saint Sebastian Interceding for the Plague Stricken (1499), by Josse Lieferinxe, housed in the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore, Maryland, since 1945. In this oil painting on wood, Lieferinxe portrays Sebastian doing a little divine obsecrating on behalf of humanity. Riddled with arrows, the saint kneels on a cloud, hands folded in prayer, as he beseeches Jesus to save the city of Pavia, Italy, from the raging Black Death in the seventh century. A larger Jesus, clad in a red robe, emerges from a much larger cloud, hand extended, as if to say, “Okay, okay. I’ll take care of this.” Below them, a flying angel and a flying demon battle it out above the city, where at least five sheet-enshrouded bodies are being prepared for burial, and a fallen grave attendant looks like the next victim. The Dutch-born Lieferinxe, often referred to as “the Master of St. Sebastian,” may have taken a creative path in presenting this striking scene to depict what, according to legend, actually occurred in Pavia in the 600s, but he certainly did with the backdrop: Lieferinxe never went to Pavia; he based the city’s appearance on that of Avignon.

The belief that St. Sebastian was a defense against the plague boosted his importance in the Late Middle Ages. Sebsatian’s survival from his “first” martyrdom by arrows played well into this belief—arrow wounds can resemble the buboes that were symptoms of bubonic plague. That comes to the fore in Saint Sebastian Interceding for the Plague Stricken (1499), by Josse Lieferinxe, housed in the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore, Maryland, since 1945. In this oil painting on wood, Lieferinxe portrays Sebastian doing a little divine obsecrating on behalf of humanity. Riddled with arrows, the saint kneels on a cloud, hands folded in prayer, as he beseeches Jesus to save the city of Pavia, Italy, from the raging Black Death in the seventh century. A larger Jesus, clad in a red robe, emerges from a much larger cloud, hand extended, as if to say, “Okay, okay. I’ll take care of this.” Below them, a flying angel and a flying demon battle it out above the city, where at least five sheet-enshrouded bodies are being prepared for burial, and a fallen grave attendant looks like the next victim. The Dutch-born Lieferinxe, often referred to as “the Master of St. Sebastian,” may have taken a creative path in presenting this striking scene to depict what, according to legend, actually occurred in Pavia in the 600s, but he certainly did with the backdrop: Lieferinxe never went to Pavia; he based the city’s appearance on that of Avignon.

#3 Madonna and Child With Saints, by Francesco and Bernardino di Bosio Zaganelli

The Walters Art Museum scores again with Francesco and Bernardino di Bosio Zaganelli’s Madonna and Child With Saints, acquired by the museum in 1931. Here, in this painting from around 1512, Sebastian appears in a grouping with Mary, the infant Jesus, and a couple of other Biblical figures. This physical propinquity of figures, known as a sacra conversazione, allows those depicted to engage in a sacred conversation. Yet, the figure on the left, Mary Magdalene, is looking to her left, out of the frame. Sebastian, on the right, also looks out of the frame, to the right. He bears a single arrow in his bare shoulder. His expression is both arresting and ambiguous, and you’ll spend some time trying to figure it out: Does he look sad yet peacefully resigned to his fate, or does he look betrayed as he turns away from his savior for whom he surrendered his life and who didn’t prevent his death at the young age of 32?

The Walters Art Museum scores again with Francesco and Bernardino di Bosio Zaganelli’s Madonna and Child With Saints, acquired by the museum in 1931. Here, in this painting from around 1512, Sebastian appears in a grouping with Mary, the infant Jesus, and a couple of other Biblical figures. This physical propinquity of figures, known as a sacra conversazione, allows those depicted to engage in a sacred conversation. Yet, the figure on the left, Mary Magdalene, is looking to her left, out of the frame. Sebastian, on the right, also looks out of the frame, to the right. He bears a single arrow in his bare shoulder. His expression is both arresting and ambiguous, and you’ll spend some time trying to figure it out: Does he look sad yet peacefully resigned to his fate, or does he look betrayed as he turns away from his savior for whom he surrendered his life and who didn’t prevent his death at the young age of 32?

#4 Saint Sebastian, by Pier Paolo Campi

Inside the Church of St. Agnes in Agony, a key part of Piazza Navona in Rome, Italy, you’ll find four chapels. The one dedicated to St. Sebastian houses this excellent marble sculpture of the saint. Completed by the Italian Baroque sculptor Pier Paolo Campi in 1719, the saint is depicted with one arm and a wrist tied to the broken post behind him. His body is pierced by four arrows. Note all his military regalia—helmet, shield, chest protector—lying at his feet, useless against his martyrdom and cast aside as he transformed from warrior to iconic Christian figure.

Inside the Church of St. Agnes in Agony, a key part of Piazza Navona in Rome, Italy, you’ll find four chapels. The one dedicated to St. Sebastian houses this excellent marble sculpture of the saint. Completed by the Italian Baroque sculptor Pier Paolo Campi in 1719, the saint is depicted with one arm and a wrist tied to the broken post behind him. His body is pierced by four arrows. Note all his military regalia—helmet, shield, chest protector—lying at his feet, useless against his martyrdom and cast aside as he transformed from warrior to iconic Christian figure.

#5 Saint Sebastian, by Antonello de Saliba

Antonello de Saliba painted Saint Sebastian in the early 1500s. It’s one of many masterpieces in Rome’s National Gallery of Antique Art in Barberini Palace, which also happens to have one of the world’s greatest ceilings. Antonello chose to portray the saint in a portrait rather than in a full-body pose. With his chest punctured by two arrows, the saint looks skyward grievously, eliciting tremendous sympathy from the viewer. Tremendous appreciation will also be elicited for Antonello’s talent when the viewer takes note of the meticulous treatment of Sebastian’s hair, every curl and lock expertly rendered.

Antonello de Saliba painted Saint Sebastian in the early 1500s. It’s one of many masterpieces in Rome’s National Gallery of Antique Art in Barberini Palace, which also happens to have one of the world’s greatest ceilings. Antonello chose to portray the saint in a portrait rather than in a full-body pose. With his chest punctured by two arrows, the saint looks skyward grievously, eliciting tremendous sympathy from the viewer. Tremendous appreciation will also be elicited for Antonello’s talent when the viewer takes note of the meticulous treatment of Sebastian’s hair, every curl and lock expertly rendered.

Five Runners-Up

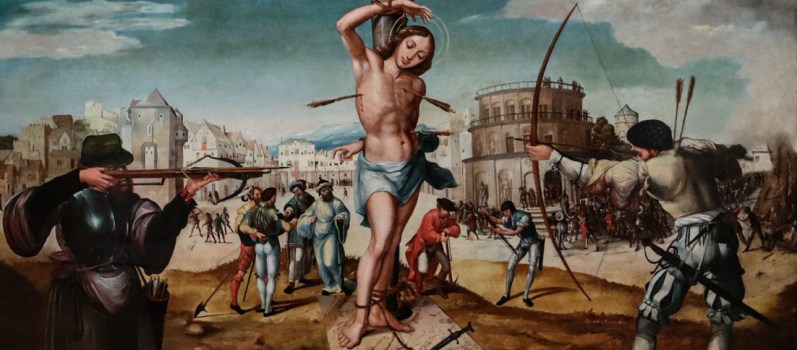

- The Martyrdom of St. Sebastian, by Gregório Lopes (National Museum of Ancient Art, Lisbon, Portugal)

- Saint Sebastian Healed by Angels, by Peter Paul Rubens (National Gallery of Antique Art, Corsini Palace, Rome, Italy)

- Saint Sebastian, by Giovanni de’ Vecchi (Church of Saint Andrew of the Valley, Rome, Italy)

- Saint Sebastian (City Hall, Brussels, Belgium)

- Saint Sebastian, by Alessandro Tiarini (Capitoline Museums, Rome, Italy)

Leave a Comment

Have you been here? Have I inspired you to go? Let me know!