On sun-kissed Malta, I was always reluctant to go inside anywhere; there was always so much to see outdoors while enjoying glorious spring weather—abundant views, festivals, markets, the eye-catching wooden balconies on homes all over the island. But then I would have missed the incredibly rich interiors of the country’s seemingly countless churches. These are my favorites.

#1 St. John’s Co-Cathedral (Kon-Katidral ta’ San Ġwann, Valletta)

The most beautiful church in Valletta, as well as its main attraction, St. John’s Co-Cathedral requires a €10 fee to enter (unless you’re attending a service), but you won’t even care from the second you enter this masterpiece. Built between 1572 and 1577 by a prominent Maltese architect, the church received its “co” status in 1816 when it was elevated to the same status as that of St. Paul’s Cathedral in Mdina, the seat of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Malta. The co-cathedral features a fairly simple exterior in the Mannerist style. Two large bell towers anchor the church, with Doric columns flanking the main doorway and supporting an open balcony, and with a couple of empty niches. An eight-point Maltese cross tops the pediment above. If it hints at a fortress more than a church, that’s probably a good thing—it withstood a devastating onslaught during World War II when Malta became the most heavily bombed place on earth.

The most beautiful church in Valletta, as well as its main attraction, St. John’s Co-Cathedral requires a €10 fee to enter (unless you’re attending a service), but you won’t even care from the second you enter this masterpiece. Built between 1572 and 1577 by a prominent Maltese architect, the church received its “co” status in 1816 when it was elevated to the same status as that of St. Paul’s Cathedral in Mdina, the seat of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Malta. The co-cathedral features a fairly simple exterior in the Mannerist style. Two large bell towers anchor the church, with Doric columns flanking the main doorway and supporting an open balcony, and with a couple of empty niches. An eight-point Maltese cross tops the pediment above. If it hints at a fortress more than a church, that’s probably a good thing—it withstood a devastating onslaught during World War II when Malta became the most heavily bombed place on earth.

Inside, it’s a completely different story. Remodeled in the 1660s, today it’s one of the finest examples of high Baroque architecture in Europe. Maltese limestone was used to construct the church, perfect for the intricate carving found throughout. The striking interior positively glows from all the gilt. The surfaces of the walls, arches, and ornamental features are encrusted with over-the-top gold frillery. Spiral columns, vivid paintings, marble of all colors, and ornate sculptures surround you. A marble group depicting the baptism of Christ adorns the main altar. The wide nave is flanked by nine side chapels—one dedicated to Our Lady of Philermos and the rest to the patron saints of the eight langues (divisions) of the Order of the Knights of the Hospital of St. John, such as saints George, Sebastian, and James—and each one richly ornamented, half of them with works by Italian artist Mattia Preti.

Inside, it’s a completely different story. Remodeled in the 1660s, today it’s one of the finest examples of high Baroque architecture in Europe. Maltese limestone was used to construct the church, perfect for the intricate carving found throughout. The striking interior positively glows from all the gilt. The surfaces of the walls, arches, and ornamental features are encrusted with over-the-top gold frillery. Spiral columns, vivid paintings, marble of all colors, and ornate sculptures surround you. A marble group depicting the baptism of Christ adorns the main altar. The wide nave is flanked by nine side chapels—one dedicated to Our Lady of Philermos and the rest to the patron saints of the eight langues (divisions) of the Order of the Knights of the Hospital of St. John, such as saints George, Sebastian, and James—and each one richly ornamented, half of them with works by Italian artist Mattia Preti.

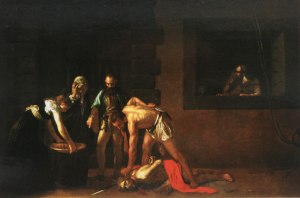

Amid all this spectacle, two of the church’s best assets completely beguiled me. One is the church’s most important piece of art: Caravaggio’s The Beheading of Saint John the Baptist, from 1608. It’s his largest piece (12’ x 17’), one of his best, and the only one he signed (in the blood spilling from John’s slit throat). A stunning example of the chiaroscuro style, it’s truly a masterpiece to behold, and it’s the one that catapulted Caravaggio onto my list of favorite artists.

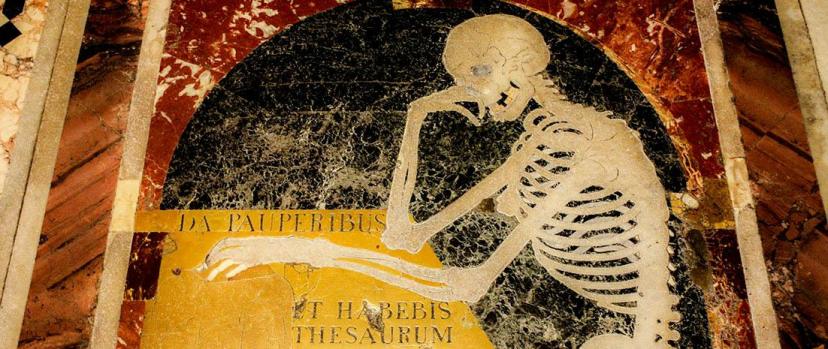

Although it’s instinctive to look up at the barrel ceiling over the nave, with its ribs separating frescoes of scenes from the life of St. John the Baptist (also by Preti), the second highlight is underfoot. The entire floor is a quiltwork of memento mori. Highly polished and richly decorated with skeletons and skulls, clocks and hourglasses, in-laid marble tomb slabs cover the floor. Below them are the remains of more than 400 Knights Hospitaller. The Knights, a medieval Catholic military order begun in Jerusalem, bounced around the Mediterranean until they received permission from the King of Spain to settle in Malta (in return for sending one Maltese falcon to the king every year on All Saints’ Day). In 1565, the Ottoman Empire invaded with a force of 40,000 men. Impossibly outnumbered (with only 8,000 soldiers plus 700 knights), Malta pulled off a miracle, dealing the Ottomans a significant defeat, albeit at a high price—nearly half the knights died in battle. They’re now buried here, with the more important knights placed closer to the altar. But, ladies, be careful what you wear when you visit: Stiletto heels are not permitted, in order to protect the fantastic artwork under you.

Although it’s instinctive to look up at the barrel ceiling over the nave, with its ribs separating frescoes of scenes from the life of St. John the Baptist (also by Preti), the second highlight is underfoot. The entire floor is a quiltwork of memento mori. Highly polished and richly decorated with skeletons and skulls, clocks and hourglasses, in-laid marble tomb slabs cover the floor. Below them are the remains of more than 400 Knights Hospitaller. The Knights, a medieval Catholic military order begun in Jerusalem, bounced around the Mediterranean until they received permission from the King of Spain to settle in Malta (in return for sending one Maltese falcon to the king every year on All Saints’ Day). In 1565, the Ottoman Empire invaded with a force of 40,000 men. Impossibly outnumbered (with only 8,000 soldiers plus 700 knights), Malta pulled off a miracle, dealing the Ottomans a significant defeat, albeit at a high price—nearly half the knights died in battle. They’re now buried here, with the more important knights placed closer to the altar. But, ladies, be careful what you wear when you visit: Stiletto heels are not permitted, in order to protect the fantastic artwork under you.

#2 St. Publius Parish Church (Knisja Arċipretali ta’ San Publiju, Floriana)

I happened to be in town for the Malta International Fireworks Festival, part of which was held in the square right outside the doors of St. Publius Parish Church, dedicated to a saint I had never even heard of, who has been Floriana’s patron saint for centuries. From my outstanding hotel, The Phoenicia, I walked all of five minutes through the enormous open square (built and expanded over the course of 200 years, from 1733 to 1990) to arrive at the church. A late-night Mass was coming to a conclusion, and as the floods of people left the church, I fought my way, salmon-like, against the human flow to make my way inside. The church was built in spasms. Although consecrated in 1792 after the second round of construction (the first started in 1733), the church wasn’t completed until after the fourth phase, ending in 1892. World War II caused some serious damage, and reconstruction that ended in the 1950s restored the church’s glory.

I happened to be in town for the Malta International Fireworks Festival, part of which was held in the square right outside the doors of St. Publius Parish Church, dedicated to a saint I had never even heard of, who has been Floriana’s patron saint for centuries. From my outstanding hotel, The Phoenicia, I walked all of five minutes through the enormous open square (built and expanded over the course of 200 years, from 1733 to 1990) to arrive at the church. A late-night Mass was coming to a conclusion, and as the floods of people left the church, I fought my way, salmon-like, against the human flow to make my way inside. The church was built in spasms. Although consecrated in 1792 after the second round of construction (the first started in 1733), the church wasn’t completed until after the fourth phase, ending in 1892. World War II caused some serious damage, and reconstruction that ended in the 1950s restored the church’s glory.

So, who was Publius? He should be better known than he actually is, at least outside of Malta. Publius, a Roman governor, welcomed St. Paul when he shipwrecked on the island in the first century. After Paul cured Publius’ father, who was afflicted with dysentery, Publius converted to Christianity and became the first bishop of Malta, leading to the creation of the first Christian nation in the West. He was martyred around 125, during the persecution of the Roman Emperor Hadrian. I especially got to like him because his feast day, in the Roman Catholic calendar, is also my birthday.

Inside, there’s a pronounced use of red, in the carpets, walls, and drapery, in the richly decorated space. The fantastic barrel ceiling is adorned with paintings depicting Paul’s shipwreck and his stay in Malta. Eight paintings fill in panels around the impressive dome, with even more around its base, and in the pendentives you’ll find paintings of such saints as Gregory and Ambrose. Stations of the Cross hang in ornate golden frames, and elaborate crystal chandeliers provide an abundance of light. Wooden sculptures of the four evangelists appear on the pulpit. You’ll also find the relics of St Publius, which have been housed here since 1768. When I had my fill of the sumptuous interior, I exited the church to join the fun in the adjacent square. A brass band was performing everything from classical music to the Star Wars theme, setting the mood for the fireworks competition that followed. All of that unfolded against the backdrop of the limestone church, with its twin bell towers, columns, clocks, balconets, arches, and pediment outlined with festive green, red, white, and yellow lights.

Inside, there’s a pronounced use of red, in the carpets, walls, and drapery, in the richly decorated space. The fantastic barrel ceiling is adorned with paintings depicting Paul’s shipwreck and his stay in Malta. Eight paintings fill in panels around the impressive dome, with even more around its base, and in the pendentives you’ll find paintings of such saints as Gregory and Ambrose. Stations of the Cross hang in ornate golden frames, and elaborate crystal chandeliers provide an abundance of light. Wooden sculptures of the four evangelists appear on the pulpit. You’ll also find the relics of St Publius, which have been housed here since 1768. When I had my fill of the sumptuous interior, I exited the church to join the fun in the adjacent square. A brass band was performing everything from classical music to the Star Wars theme, setting the mood for the fireworks competition that followed. All of that unfolded against the backdrop of the limestone church, with its twin bell towers, columns, clocks, balconets, arches, and pediment outlined with festive green, red, white, and yellow lights.

#3 Cathedral of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary into Heaven (Katidral ta’ Santa Marija Assunta, Victoria)

I hopped aboard a ferry across impossibly blue Mediterranean waters to the Maltese island of Gozo and then took a bus to the Citadel, the walled, older section of the city of Victoria. Almost immediately, I was standing in front of the giant staircase leading up to the Cathedral of the Assumption. This church goes way, way back, to when it was (in a very different form) a Roman temple dedicated to Juno. Then it became a Christian church, then a Byzantine church (destroyed by the Arabs), then another church (sacked by the Ottomans), and then yet another church (badly damaged in an earthquake). With a history like that, it’s no wonder that its dedication, when the present church was completed in 1711, lasted a full 24 hours. Halfway up the stairs, I passed by the two tall statues of popes Pius IX and John Paul II. I gazed up at the cream-colored façade, with Corinthian pilasters, a heavy cornice dividing the two tiers, and a niche with a white statue of Mary, added in 1851. Inside, pilasters raised on tall platforms support the barrel ceiling, adorned with paintings of scenes from the life of Mary. There’s a bulbous marble baptismal font, gorgeous marble tomb slabs on the floor, and a wonderful trompe-l’oeil deception above you—a flat painting that you’d swear is the three-dimensional dome constructed with columns, brackets, soffits, windows, and an oculus. At its base, look for Judith triumphantly holding the decapitated head of Holofernes. For an extra treat, I went back outside and scrambled along the tops of the walls around the cathedral, dotted with cannons and ruins, to see the sole campanile and the buttresses that are virtually invisible from street level.

I hopped aboard a ferry across impossibly blue Mediterranean waters to the Maltese island of Gozo and then took a bus to the Citadel, the walled, older section of the city of Victoria. Almost immediately, I was standing in front of the giant staircase leading up to the Cathedral of the Assumption. This church goes way, way back, to when it was (in a very different form) a Roman temple dedicated to Juno. Then it became a Christian church, then a Byzantine church (destroyed by the Arabs), then another church (sacked by the Ottomans), and then yet another church (badly damaged in an earthquake). With a history like that, it’s no wonder that its dedication, when the present church was completed in 1711, lasted a full 24 hours. Halfway up the stairs, I passed by the two tall statues of popes Pius IX and John Paul II. I gazed up at the cream-colored façade, with Corinthian pilasters, a heavy cornice dividing the two tiers, and a niche with a white statue of Mary, added in 1851. Inside, pilasters raised on tall platforms support the barrel ceiling, adorned with paintings of scenes from the life of Mary. There’s a bulbous marble baptismal font, gorgeous marble tomb slabs on the floor, and a wonderful trompe-l’oeil deception above you—a flat painting that you’d swear is the three-dimensional dome constructed with columns, brackets, soffits, windows, and an oculus. At its base, look for Judith triumphantly holding the decapitated head of Holofernes. For an extra treat, I went back outside and scrambled along the tops of the walls around the cathedral, dotted with cannons and ruins, to see the sole campanile and the buttresses that are virtually invisible from street level.

#4 Metropolitan Cathedral of Saint Paul (Il-Katidral Metropolitan ta’ San Pawl, Mdina)

The fortified city of Mdina is like a microcosm of Malta’s history: It was founded by Phoenician settlers who called it Maleth. The Romans took over, renaming it Melite, before the Arabs replaced them, when it came to be known as Mdina (from the Arabic medina). It was the capital of Malta from antiquity to the medieval period, then began centuries of decline, earning it the popular nickname “Silent City.” Indeed, as a I wandered its quiet alleys that immediately conjured up visions of the Mideast, I felt a profound serenity. With a population of barely 100 within its walls, Mdina feels delightfully empty. One of its highlights is St. Paul’s Cathedral. Rebuilt in 1705 after a massive earthquake centered in nearby Sicily, the Baroque structure stands, allegedly, on the spot where Roman governor Publius (and eventual Catholic bishop and saint) met St. Paul after his shipwreck. Anchoring a lovely square, the cathedral features three bays divided by Corinthian pilasters, with the central bay projecting forward just slightly and the framing two bays leading up to the twin bell towers. The octagonal drum features eight stone scrolls and a red roof, topped by a lantern. Inside there are two side aisles and two side chapels. I walked down the central aisle along inlaid tombstones and commemorative marble slabs, lasting testaments to the bishops, canons, noble families, and laymen buried beneath. In the 1790s, three Sicilian painters—all brothers—created the ceiling frescoes depicting the life of St. Paul. Murals of the four evangelists, hard at work creating the Gospels, decorate the pendentives at the base of the dome, which has the fresco The Glory of St. Peter and St. Paul, not added until the 1930s. Much older are the 15th-century choir stalls, the baptismal font from 1495, and the main door through which I had passed, made in 1530.

The fortified city of Mdina is like a microcosm of Malta’s history: It was founded by Phoenician settlers who called it Maleth. The Romans took over, renaming it Melite, before the Arabs replaced them, when it came to be known as Mdina (from the Arabic medina). It was the capital of Malta from antiquity to the medieval period, then began centuries of decline, earning it the popular nickname “Silent City.” Indeed, as a I wandered its quiet alleys that immediately conjured up visions of the Mideast, I felt a profound serenity. With a population of barely 100 within its walls, Mdina feels delightfully empty. One of its highlights is St. Paul’s Cathedral. Rebuilt in 1705 after a massive earthquake centered in nearby Sicily, the Baroque structure stands, allegedly, on the spot where Roman governor Publius (and eventual Catholic bishop and saint) met St. Paul after his shipwreck. Anchoring a lovely square, the cathedral features three bays divided by Corinthian pilasters, with the central bay projecting forward just slightly and the framing two bays leading up to the twin bell towers. The octagonal drum features eight stone scrolls and a red roof, topped by a lantern. Inside there are two side aisles and two side chapels. I walked down the central aisle along inlaid tombstones and commemorative marble slabs, lasting testaments to the bishops, canons, noble families, and laymen buried beneath. In the 1790s, three Sicilian painters—all brothers—created the ceiling frescoes depicting the life of St. Paul. Murals of the four evangelists, hard at work creating the Gospels, decorate the pendentives at the base of the dome, which has the fresco The Glory of St. Peter and St. Paul, not added until the 1930s. Much older are the 15th-century choir stalls, the baptismal font from 1495, and the main door through which I had passed, made in 1530.

#5 Sanctuary Basilica of the Assumption of Our Lady (Santwarju Bażilika ta’ Santa Marija, Mosta)

The public bus let me out across the street from the Sanctuary Basilica of the Assumption of Our Lady in the city of Mosta. This limestone church, commonly referred to as Mosta Dome, was completed in 1860, based on the design of the Pantheon in Rome, and it’s easy to see the similarities. I stood facing the main entrance, admiring the portico with half a dozen Ionic columns that support the carved entablature and the pediment adorned with acroterions; the two bell towers; and the curvature of the structure behind them. This is clearly a solid structure—its walls measure up to 30’ in thickness. I stepped inside and was almost immediately in the rotunda, staring up at the third-largest unsupported dome in the world, surpassed only by the Pantheon and the Rhode Island State Capitol in Providence. Measuring a whopping 122’ across, the dome features an oculus surrounded by what could pass for the ray florets of a sunflower, and hundreds of gilded rosettes set in panels of blue framed in gold. The design is repeated over the eight niches around the church, including the deepest, the bay that holds the main altar, approached by an undulating marble staircase. In this one vast room, amid all the stucco moldings and gilded and decorative elements, there’s plenty of art to admire, too—murals, paintings, sculptures. If you’re looking for any sort of miracle in your life, this might be just the place to ask for one: In 1942, Germany dropped three aerial bombs on the church: two were deflected and didn’t go off; the third pierced the dome and landed in the church during Mass being celebrated by 300 people—and failed to explode.

The public bus let me out across the street from the Sanctuary Basilica of the Assumption of Our Lady in the city of Mosta. This limestone church, commonly referred to as Mosta Dome, was completed in 1860, based on the design of the Pantheon in Rome, and it’s easy to see the similarities. I stood facing the main entrance, admiring the portico with half a dozen Ionic columns that support the carved entablature and the pediment adorned with acroterions; the two bell towers; and the curvature of the structure behind them. This is clearly a solid structure—its walls measure up to 30’ in thickness. I stepped inside and was almost immediately in the rotunda, staring up at the third-largest unsupported dome in the world, surpassed only by the Pantheon and the Rhode Island State Capitol in Providence. Measuring a whopping 122’ across, the dome features an oculus surrounded by what could pass for the ray florets of a sunflower, and hundreds of gilded rosettes set in panels of blue framed in gold. The design is repeated over the eight niches around the church, including the deepest, the bay that holds the main altar, approached by an undulating marble staircase. In this one vast room, amid all the stucco moldings and gilded and decorative elements, there’s plenty of art to admire, too—murals, paintings, sculptures. If you’re looking for any sort of miracle in your life, this might be just the place to ask for one: In 1942, Germany dropped three aerial bombs on the church: two were deflected and didn’t go off; the third pierced the dome and landed in the church during Mass being celebrated by 300 people—and failed to explode.

Five Runners-Up

- St. George’s Basilica (Il-Bażilika ta’ San Ġorġ, 1678, Victoria)

- Basilica of St. Dominic (Il-Bażilika ta’ San Duminku, 1815, Valletta)

- St. Francis of Assisi Church (San Franġisk t’Assisi Knisja, 1681, Valletta)

- Collegiate Church of Saint Lawrence (Knisja kolleġġjata ta’ San Lawrenz, 1697, Birgu)

- Collegiate Church of the Immaculate Conception (Il-Knisja Kolleġġjata tal-Immakulata Kunċizzjoni, 1730, Cospicua)

Leave a Comment

Have you been here? Have I inspired you to go? Let me know!