Logan Street is only one-third of a mile in length, but in that short span it rises 256’, with an average grade of 15.6%. That’s quite a hike for a city street—compare it to famously hilly San Francisco, which, with a few exceptions, averages a grade of less than 10%. Bicyclists face its challenge in the annual Dirty Dozen race as they confront a baker’s dozen of 13 of the steepest hills in the Pittsburgh metropolitan area, including Logan Street.

At the very base of Logan Street stands St. Nicholas Croatian Catholic Church, and I faced no challenge whatsoever getting there—a four-mile taxi ride from my hotel in Pittsburgh, the Hotel Monaco, deposited me directly at the entrance of the church.

This year, as the world acknowledges the end of World War II 80 years ago, St. Nicholas is also celebrating another milestone, its 125th anniversary. I was there a few years prior, specifically to take a tour to view the most shocking fresco murals I’ve ever seen in a church.

The current church is the second St. Nicholas Croatian Catholic Church on this spot, the first having burned down in 1921 (attributed to arson), 21 years after it was erected as the first purposely built Croatian Catholic church in the United States. This newer version—a symmetrical structure in beige brick with twin bell towers—was completed in 1922, just as Millvale’s population, still with a very healthy dose of Croatians, was peaking at about 8,100. (That has since dwindled down to about 3,400.)

About a decade after its completion, the church was still struggling to pay off its construction debt, so a priest from another Croatian church nearby was transferred here, based on his success at clearing his now former’s church’s debt. It was Father Albert Zagar who invited Maksimilijan “Maxo” Vanka to decorate the church, as he was sure the Zagreb-born Vanka would understand the parish’s cultural background. That choice ultimately put the church on the National Register of Historic Places in 1980.

At first, St. Nicholas appears to be a regular church—a statue of St. Roch, pointing to his leg wound; simple but lovely carved-wood Stations of the Cross; abstract designs in the stained-glass windows. But when the 45-minute tour began, I knew I was in no ordinary church. Vanka’s iconoclastic murals, which cover 11,000 square feet of the church’s walls and ceilings, are simply extraordinary.

After marrying an American who was touring the Balkans in 1931, Vanka—a corresponding member of the Croatian Academy of Sciences and Arts—and his wife and daughter moved to New York in 1935. Shortly after, he was tapped for the St. Nicholas job. Vanka completed the first of two sets of murals in record time, from April to June 1937, forgoing meals and working every day until way past midnight, despite his belief that the church was haunted by a ghostly figure in a black robe.

Vanka’s first series topples conventional notions of what ecclesiastical art should look like. In a distinctive Byzantine style, Vanka did create some traditional scenes—the Four Evangelists and the disciples on the ceiling, for instance, and Mary, Queen of Croatia (wearing the traditional red and blue colors of Croatia) behind the altar. To the left of Mary, Pastoral Croatia depicts a rural family in a typical Croatian village, standing and prostrate in traditional garb, beside their little picnic, praying to Mary.

Things get a little more curious with the mural on the right, Croatians in America, which shows Croatian immigrant men in overalls, holding shovels, picks, and a metal lunch box standing before the polluting smokestacks that virtually destroyed Pittsburgh’s environment for decades, being led by Fr. Zagar himself as he beseeches Mary to watch over the laborers in their often dangerous and unhealthy jobs.

The Crucifixion shows two angels, covering their faces with one hand while the other holds a goblet being filled with the blood dripping from Christ’s wrists. A Roman soldier poses on the left, while a grieving Mary on the right stands before the strangely colored sun, representing the eclipse that occurred when Christ died on the cross. Below Christ’s feet, the dead start to rise, crypts being shattered by lightning bolts from the sky. In The Pieta, an oversized Mary holds her undersized son while seven daggers take aim at her back, signifying her Seven Sorrows that unfold in the New Testament.

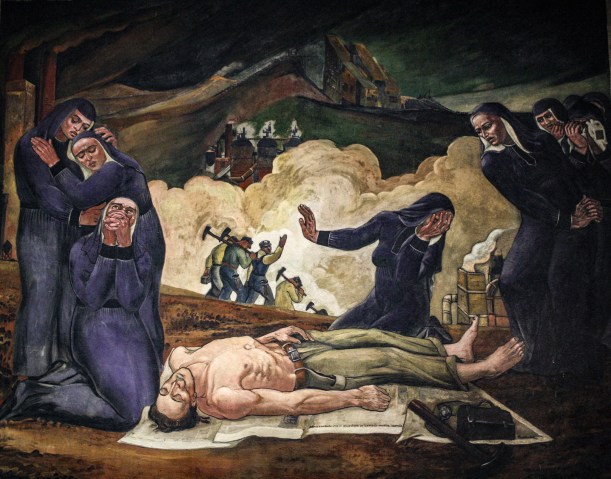

Religious dogma is virtually discarded in Vanka’s final two pieces from this initial installment. Immigrant Mother Raises Her Sons for American Industry shows a lifeless, shirtless young man lying on the ground, a mining disaster victim. A group of women in identical somber blue scapulars and cowls surround him while, in the background, laborers continue their march toward Pittsburgh’s relentlessly belching smokestacks. In Croatian Mother Raises Her Son for War, a grieving mother sits beside the coffin containing the body of her dead son, still in military uniform and with a bandage spotted with blood on his head. Dressed in the traditional mourning outfit of white gowns and headcovers, she’s accompanied by eight other women, dressed identically. Behind them, another casket is being carried toward a hilltop church, in between graveyard rows of little white crosses.

These, clearly, are not what one expects to find in a Catholic church, and I found them to be absolutely riveting. But Vanka wasn’t done yet. He was asked back to St. Nicholas for a second collection of murals, bumping the total up to 25. Again, he includes traditional depictions, St. Francis and St. Claire among them. In Old Testament, a lightning bolt shatters the golden calf, terrifying the idolatrous worshippers around it; on the right, a flaming hand reaches out from heaven and bestows upon a fierce-looking Moses the two tablets of the Ten Commandments. New Testament shows Jesus passing off the keys to His kingdom to Peter via an angel beneath an all-seeing eye, while another angel zaps a demon, complete with serpent, with another lightning bolt.

In addition to these works, Vanka brought more than his talent—he brought his personal history, and with it, more ferocious images, some of which come with a twist. As part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire in World War I, Croatia fought alongside the Central Powers against the Allied Powers, including the United States. Being a pacifist, Vanka rejected service in the regular army and then jumped ship to serve on the other side, with the Belgian Red Cross. Now, having survived the war to supposedly end all wars and seen firsthand its horrors, Vanka was completing his murals in the United States by 1941 while World War II was raging in Europe. Once again, the now Independent State of Croatia found itself on the wrong side, as a puppet state created by the Axis Powers and fighting for the German Nazis and Italian Fascists, even though the Yugoslav Partisan movement, including many Croatians, went against the Axis. Vanka’s history presents some disquieting images for an American viewer: It’s the Allies, not the Axis Powers, committing the atrocities in his paintings.

In Christ on the Battlefield, an Allied soldier punctures the abdomen of a rather shocked-looking crucified Christ while another soldier raises a weapon high above his head to continue the carnage. In the astonishing Mary on the Battlefield, Mary engages with Allied soldiers, grabbing the bayonet pointed at her chest with one hand while holding a knife in the other as a gun-toting soldier approaches her from the rear.

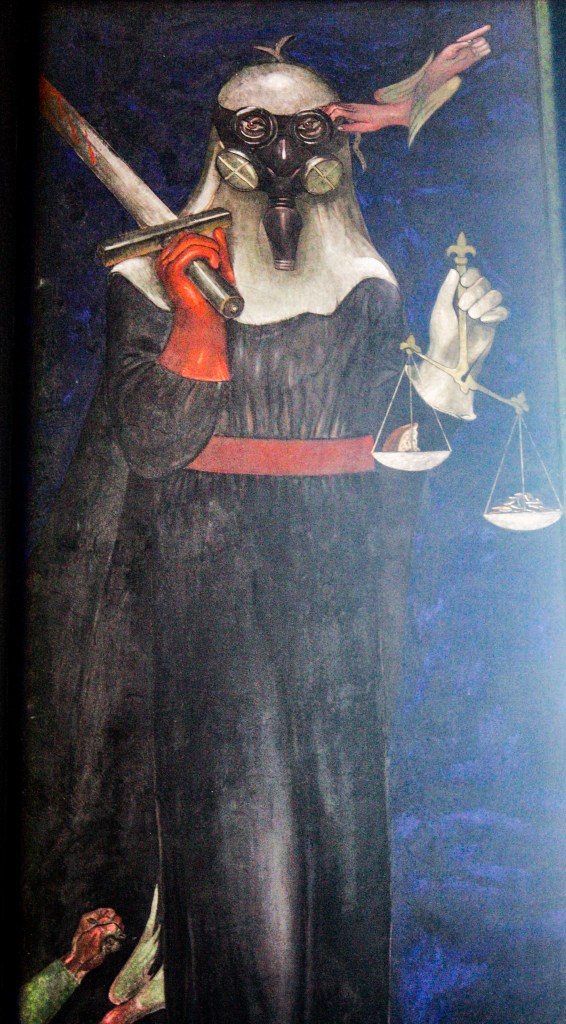

In Justice, an angel points heavenward while holding a perfectly balanced scale in his right hand. In Injustice, however, a hooded figure in a black robe wearing a gas mask and brandishing a bloody sword shows a disturbingly unbalanced scale in his left (sinister) hand, with gold coins outweighing bread.

The striking juxtaposition of two more murals encapsulates Vanka’s sensibilities of war, its causes, and the unfairness of the world. The Simple Family Meal portrays exactly that, a family of six partaking outdoors of a very basic meal of bread and perhaps a hot dish of some sort, with an ephemeral Jesus standing behind them, hands raised in a blessing. Its counterpart, The American Capitalist, presents a wealthy American businessman sitting alone before an elaborate meal being brought to the table by a black servant. Dressed exceptionally well for his meal (top hat, cape, monocle, pinkie ring), the man peruses the stock pages while he ignores a beggar at the opposite end of the table. An angel covers its eyes and looks away in sadness and disgust—a blatant condemnation of greed and materialism in the United States.

These beautiful, disturbing, and exceptionally thoughtful works of art present both the terrors and injustices of the world, but they also acknowledge the Christian promise of redemption out of suffering via the 520-square-foot Transcendent Vision (Including Disciples) on the ceiling, in which Christ ascends into heaven, surrounded by angels and constellations, creating a divine vision of eternal reward.

Vanka had never painted in a church before this collection. He considered his murals a gift to America, which, in turn, promptly forgot about him following his death in 1963. Three decades later, some artists and critics began comparing his work to that of renowned Mexican muralist Diego Rivera. Renewed attention to Vanka launched the founding of the Society to Preserve the Millvale Murals of Maxo Vanks, which has taken up the herculean task of restoring and preserving the murals that have faced decades of smoke, atmospheric salts, damaging sunlight, grime, and water leaks.

Those were all good signs, until Donald Trump’s idiotic DOGE cutbacks threatened maintenance of these priceless murals by cutting off funding that had already been earmarked for the work. In this sciolist’s mind, the slashed budget makes perfect sense because Vanka illustrated themes that are anathema to Trump’s questionable and inexorable philosophies: the evils of American materialism and portraying the United States and its dwindling number of friends in a poor light, the travesty of injustice, the suffering of the poor and powerless, and nonconformist works that challenge the revered, all created by a bastard—Vanka was born out of wedlock. Hopefully, as soon as the mendacious Trump’s disastrous reign as dictator-president is over (if not sooner), smarter heads will prevail, restorative work will continue, and Vanka’s unique works will live on for all to enjoy, marvel at, and learn from.

I’d Love to Hear From You!

Have you been here? Have I inspired you to go? Let me know!