From abstract designs on the façades of apartment buildings, to the gorgeous historic panels in Porto’s São Bento railway station, to massive displays depicting religious scenes both inside and outside the country’s churches, blue-and-white tilework abounds in Portugal. I was instantly enthralled.

I was already familiar with the craft. I distinctly remember the small teacups in my family’s favorite Chinese restaurant from when I was a child, the sides decorated with abstract blue-and-white patterns. And when I was in the Netherlands a few years ago, I fell in love with the Delftware that the Dutch made famous in the 1600s. But the art form goes back farther than that: Artisans in Iraq were adding blue glazes to imported Chinese white stoneware in the ninth century, and the Chinese themselves originated it in the seventh century.

To learn more about it, and to see some spectacular examples, I hopped on a bus from my hotel for a 20-minute ride, mostly along the Tagus River, to the National Tile Museum (Museu Nacional do Azulejo). A visit here is doubly rewarding: Not only is it home to one of the largest collections of ceramic tile in the world, it’s also housed in a gorgeous centuries-old former convent.

I took my place at the end of the short line forming in the small courtyard at the museum’s entrance, contemplating the cheery orange trees, the large urns, the palm trees, and the decaying walls around me. Dedicated to the art of azulejo—traditional tilework of Portugal and the Portuguese Empire—the National Tile Museum is housed in the former Mother of God (Madre de Deus) Convent, founded by Queen Leonor in 1509. Partially destroyed during the catastrophic earthquake of 1755, it was reconstructed on an even grander scale. Purchased by the state and closed in 1867 with the intention of transforming it into a museum in honor of Leonor’s 500th birthday, the convent’s new owners missed the mark by about seven years. The museum was established in 1965 and was elevated to a national museum 15 years later.

After purchasing my ticket, I stepped outside into the King João III Cloister, an open square with rose bushes and a central stone fountain, surrounded by a simple arcade. From here, rooms led me along a chronological path in the development of azulejo in the 15th century, beginning with information about the materials and techniques used to manufacture tiles. On display are dazzling examples of ceramic tiles, porcelain, and faience (fine tin-glazed pottery) that extend beyond Portugal—15th- and 16th-century floor and wall azulejos from Spain, for instance, and palatial panels made in Antwerp. The items here are more colorful than the blue-and-white combination so clearly favored in Portugal: Blue is still predominant, but there’s a healthy dose of green and especially yellow.

Portuguese examples begin with the Our Lady of Life altarpiece, a beautiful Nativity scene from 1580, featuring the Holy Family, a couple of barnyard animals, and a shepherd bearing a basket of eggs, flanked by two of the four Evangelists. Considered one of the earliest masterpieces of tile art, it uses shading to create the illusion of depth.

The exhibits progress into the 17th century, with patterned azulejos, mainly commissioned by the Church, laid out in carpet styles with distinct borders, as well as religious panels for altar frontals.

From there, I entered the King Manuel Room, with its collection of tile panels portraying mystical scenes from the life of St. Francis, attributed to Manuel dos Santos, one of the most important tile masters of the early 18th century. That room flows into the Lower Choir of the church, encrusted in gold and lined with the blue-and-white tiles I was anticipating, including an impressive Crucifixion scene.

I climbed up the deep stairs and entered the church itself, a magnificent Baroque interior, aglow in gold, with a high choir with rich carved gilt wood embellishments, wide pastoral and idyllic scenes in blue-and-white azulejo, and abundant paintings depicting the lives of the Virgin Mary, St. Francis, and St. Clare.

The high altar leads to the Grand Staircase, lined halfway up the walls on either side with tiles that follow the angle of the staircase itself. On the second floor, I immediately became engrossed in the collection from the late 1600s and early 1700s: Christ Giving the Keys to Saint Peter, featuring a Jesus with incredibly ripped abs that would make any Men’s Health cover model jealous; Saint Lawrence’s Martyrdom; The Birth of Saint Anne; and The Triumph of David, with the outsized victor carrying Goliath’s decapitated head.

There’s plenty of secular and nonreligious works here, too, like The Cortege of Neptune and Amphitrite and Battle of Alexander of Macedonia Against Darius of Persia at Issus.

I found two works particularly amusing: In The Leopard Hunt, from around 1665, a leopard is lured into an open box, its lid held up by a string, attracted by a mirror reflecting an image of itself. In The Chicken’s Wedding, also from around 1665, a chicken in a royal carriage is making her way to her wedding in a procession of coach-driving, instrument-playing, pipe-smoking, fashionably dressed monkeys. Although comical, this latter one is really about royal pomposity and human toadyism, which mostly likely got the artist into some trouble more than 300 years ago.

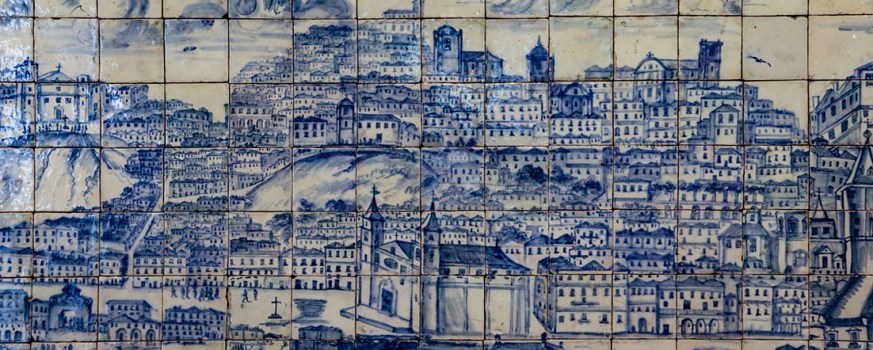

All of this leads up to the museum’s pièce de résistance. In a room that also includes more contemporary works from the 1900s, I found Great Lisbon Panorama Before the Earthquake of 1755. This blue-and-white composition of 1,300 tiles measures 75’ in length—the longest tile piece in Portugal. Created in the early 1700s, it depicts about nine miles of the Lisbon skyline at the time from the vantage point of the Tagus River. Not only is it an astounding piece of art, it’s also an important historical document: No more than 50 years after it was created, the Great Earthquake of 1755 decimated Lisbon and ushered in the collapse of the Portuguese Empire. This work shows what the city looked like prior to its destruction, and as I slowly walked from one end to the other, captivated by painstaking and realistic detail—from balconets on municipal buildings to the cannons at Belém Tower—I tried to pick out all the buildings I had seen in Lisbon so far as well as the ones that are gone forever.

By the time I was ready to leave, I had gained a greater appreciation and understanding of azulejo, which would serve me well as I departed Lisbon and traveled north to Porto, where its use is even more liberal and striking. The museum’s exhibits affirm the azulejo tradition as still relevant to Portuguese culture. If you’re in any doubt about that, pop into the museum’s café-like restaurant in the former refectory: The walls are lined with blue-and-white tiles depicting fish, game, and poultry hanging on a rod, ready to be cooked for your pleasure.

Leave a Comment

Have you been here? Have I inspired you to go? Let me know!