Somehow, I managed to earn my bachelor’s degree in English without ever having read Mark Twain. So, when I found myself in Hartford, Connecticut, I decided to familiarize myself with more than just the basics about him that I already knew—his birthplace, his real name, his iconic white suit and hair.

Just over a mile’s walk from my hotel, the Goodwin Hotel in downtown, the Mark Twain House took me by surprise. I wasn’t expecting something so grand or so huge as the home of one of the United States’ greatest humorists and writers. I was instantly impressed, and I was eager to learn a lot more about him.

My education began on my way to the museum, one of three buildings on the property. I passed by one of the 11 gardens on the grounds, which informed me that Twain was interested in bees, so much so that he wrote an essay about them in 1902.

Past the Nook Café, where you can purchase sandwiches, salads, baked goods, and snacks sourced from local food vendors while you note one of Twain’s gnomic quotes on the wall (“A full belly is little worth where the mind is starved.”), I made my way down the gently descending staircase, accompanied by some of his witticisms on the walls: “Always obey your parents when they are present,” “The man with a new idea is a crank until the idea succeeds,” “Architects cannot teach nature anything,” “There is nothing sadder than a young pessimist, except an old optimist.”

I proceeded to the large gallery with a permanent exhibit about Twain’s life and work, from his birth as Samuel Clemens in Missouri to his successes (and failures) as a riverboat pilot, miner, journalist, lecturer, entrepreneur, publisher, and inventor. The exhibit also introduced me to this polymath’s prolific travel experiences that put mine to shame. During his life, Twain went all over the United States, from Buffalo to the American West to Hawaii, as well as to such far-flung places as Canada, the Mediterranean, Europe, the Middle East, Australia, New Zealand, Fiji, Sri Lanka, India, Mauritius, and South Africa.

In addition to being exceptionally well traveled, Twain was also a supporter of technological progress and commerce, but he was against welfare; he was pro–labor union but also, for a time, an imperialist; he supported women’s suffrage and the abolition of slavery but held strongly negative attitudes toward Native Americans and Catholics. He was, more than I ever knew, a collection of contradictions.

My guided tour—an unexpected private one, as I was the only person to show up for the 11 a.m. tour—began in the museum and quickly headed outside, to the Carriage House, the second building on the grounds, where the coachman and his large family used to live, from the looks of it, quite comfortably.

Then it was on to Twain’s house itself via the stone and gravel paths. This magnificent home, completed in 1874 for the Clemens family (and paid for with Mrs. Clemens’ abundant inheritance), is one of the grandest and visually arresting buildings in Hartford. Technically, its style is Victorian Gothic revival, with a steeply pitched roof and an asymmetrical bay window layout. One of Twain’s biographers called it “part steamboat, part medieval fortress and part cuckoo clock.” I’d have to agree—it’s a rather eclectic mix, pulled together by unique brickwork, wooden balconies, distinctive chimney stacks, and a generous wraparound porch with railing flowerboxes called the Ombra (Italian for “shade”).

My guide granted me entry into the 25-room home, spread out over 11,500 square feet on three floors, with a total of 41 steps up to the top floor. It was here that Twain spent his happiest and most productive years of his life, although it may not have started that way.

Born in 1835, Samuel Clemens adopted Mark Twain as his pen name in 1863 and married Olivia Langdon in 1870—a very happy union, and a financially beneficial one on his part. The couple spent about $45,000 to build the house, a sum that frustrated Twain as it always seemed to be rising, even though it was Olivia’s inheritance that funded the construction and furnishings. They moved in on the heels of the death of their first child, a son who lived only 19 months before dying in 1872. They had three more children, all girls, who brought life to the house and great pleasure to Twain—and, ultimately, heartache.

The house tour begins in the impressive Entrance Hall, with its grand staircase, wainscoting in silver, fine woodwork, and ceilings and walls painted in red with patterns of black and silver. Much of the family’s original furniture and possessions are on display, evident immediately in the adjacent Drawing Room. Formal entertaining was held in this room, with silver East Indian stenciled motifs over the salmon pink walls and ceiling. An ornate chandelier, tufted furniture, and a large pier glass mirror, all belonging to the family, fill up the room nicely.

The ground floor also houses the Dining Room, with walnut paneling and doors with fine stenciling based on Chinese motifs. The walls resemble tooled leather—a sign of wealth—but they’re actually covered with red and gold paper to simulate the look of leather, which was more in line with the Clemens’ construction budget at the time.

A round glass conservatory, which the Clemens girls called “The Jungle,” was filled with a fountain and lush flora. The Mahogany Room was a guest suite, complete with bedroom, dressing room, and bathroom, but it also served as a space for family theatricals (the young girls were outgoing performers) and for Olivia’s gift-wrapping duties.

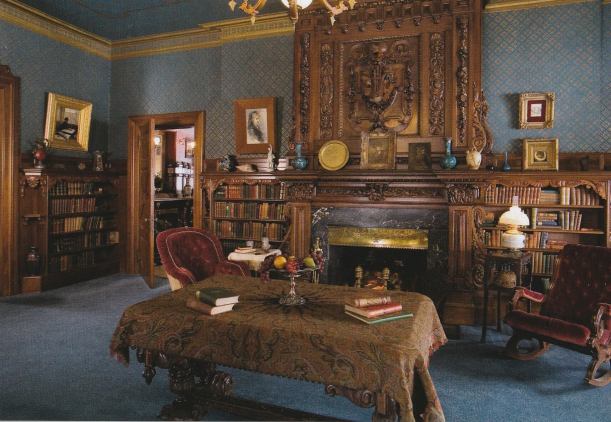

I found the library to be one of the house’s most interesting rooms. Here, Twain would recite poetry, tell stories, and present excerpts from his new works to family and friends. Twain and Olivia purchased the large oak mantelpiece from a Scottish castle specifically for the fireplace in this room, but the top was too high for the ceiling, so it was dismantled and placed over a doorway. Twain’s daughters would demand that their father tell them stories based on the objects placed along that mantlepiece—in the order they were arranged, and in stories that always had to be different. Twain happily obliged.

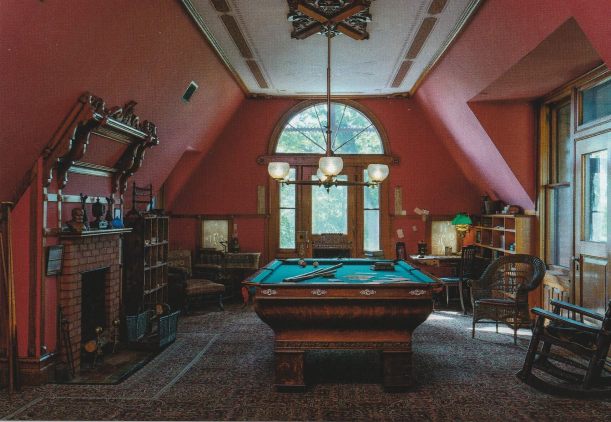

The tour continued to the two upper floors, to the Clemens Bedroom, with its ornately carved bed purchased in Venice (Twain would die in this bed in a different home, in 1910 at age 74); the Nursery; the School Room, where the Clemens girls were homeschooled in German, history, arithmetic, and geography, among other subjects; and the Billiard Room, which functioned as Twain’s office, study, and private entertainment space. Away from the activity of the busy household below, this room and its relative quiet enabled Twain both to write his greatest works—The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, The Prince and the Pauper, Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, and A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court—and to entertain friends, sometimes into the early-morning hours, with billiards, cigars, and hot Scotch.

Twain and his family, although they truly loved this home, didn’t reside here for a particularly long span. In fact, their residence lasted only 17 years, until they moved out of the house in 1891 and eventually sold it in 1903, about a year before Olivia died. Their departure wasn’t entirely voluntary—despite Twain’s growing success, severe financial problems rendered the house unsustainable. In addition to his hemorrhaging publishing house, one of Twain’s most spectacular failures was his huge investment in the Paige Compositor, a massive typesetting machine, “marvelously ingenious and perfect, from a mechanical standpoint; worthless commercially, the costliest machine ever built,” according to the New York Evening Telegram in the late 1800s. Only two of these machines were ever built, costing Twain $300,000, and they went nowhere, bankrupting him and decimating most of his book profits as well as a big chunk of his wife’s inheritance.

To recoup his losses, the Clemens family embarked on an extended tour through Europe, where Twain tried to revitalize his bank accounts through speaking engagements. While away, his eldest daughter, Susy, who had remained in Hartford, died of spinal meningitis at age 24 in 1896; her death was the main reason why Twain and Olivia never returned to the home—the loss of their daughter was just too painful. More pain was to come in 1909, when the youngest daughter, Jean, died in a bathtub, either from an epileptic seizure (from which she had suffered starting at age 15) or heart failure. Only middle daughter Clara outlived Twain, surviving until 1962. As none of the girls had children, Twain had no direct descendants past his own children.

After the house was sold, the new owners rented it out as a school for boys for five years. In 1922, it became an apartment building, until 1930, when the house, threatened with demolition, was saved largely through the efforts of Katharine Seymour Day, a niece of Harriet Beecher Stowe. Until 1956, the ground floor of the house served as the Mark Twain Branch of the Hartford Public Library while the upper floors continued as apartments until the 1960s. In 1963, when the house was designated National Historic Landmark, serious efforts began to restore it to the original, a herculean task that lasted a full decade. Since then, there have been a number of shortfalls, setbacks, and successes, but since 2011, the house and museum have been on solid footing, open to tens of thousands of visitors annually.

My tour ended as my guide escorted me back outside. I was so much richer for the hourlong tour, primed to pick up copies of some of his works and one of his biographies at the well-stocked gift shop in the museum. Before Twain even had this home built, he wrote about Hartford, in 1868, “Of all the beautiful towns it has been my fortune to see this is the chief.” One of the most celebrated authors in American literature added to this beauty with the construction of his home—and it’s standing in all its glory for you to experience.

Leave a Comment

Have you been here? Have I inspired you to go? Let me know!